The “megaquake” warning that Japan issued last week sparked a new debate among US seismologists about when and how to alert West Coast residents to an increased chance of a significant earthquake.

Japan Megaquake warning after the earthquake

A magnitude-7.1 earthquake occurred on August 8 at 16:42 local time, striking southern Japan. After the earthquake struck off the coast of the mainland island of Kyūshū, almost a million people felt it all around the region, and at first there was concern that a tsunami might come. However, nothing more than a small wave washed ashore, the buildings held, and no one perished. The situation passed almost as soon as it started.

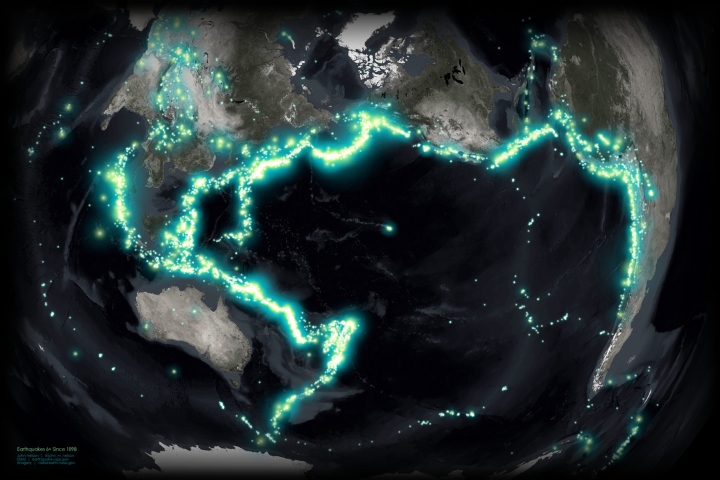

However, something novel transpired. An official government agency, the Japan Meteorological Agency, issued the first-ever “megaquake advisory.” These two words might seem unsettling, and they kind of are. Beneath the waters of Japan lies a massive rift where two tectonic plates collide, posing a ticking time bomb. This border has been experiencing stress for a while, and eventually it will do what it has done time and time again: a portion of it will violently break, causing a severe earthquake and possibly a massive tsunami.

The magnitude 7.1 earthquake may be a precursory quake, or foreshock, to a much greater one that might create a tsunami that could kill a quarter of a million people, which is why the advisory was issued in part.

For the time being, scientists believe it is highly unlikely that the magnitude-7.1 earthquake was a precursor to a cataclysmic event. Although nothing is certain, Harold Tobin, the director of the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network, states that “the chances that this actually is a foreshock are really quite low.”

U.S. seismologists worried about the west coast

The warning caused beach closures, the cancellation of fireworks festivities, and train delays in Japan. People scrambled to get supplies in case of emergencies. Tobin stated, “We don’t have such a protocol” in the United States. But the Cascadia subduction zone is one of our equally deadly faults.

The Cascadia fault’s magnitude 9.0 earthquake and the ensuing wave, according to the Federal Emergency Management Agency, would kill 14,000 people in Oregon and Washington.

But in the event of a lesser earthquake similar to the one that struck Japan recently, seismologists would have to make a snap decision about whether and how to notify the public.

Tobin has been considering this situation for years: What justifies raising the alarm if he discovers evidence, even if it’s tiny, that a catastrophic earthquake is more likely? Should you cry wolf if the chances are against you?

Scientists having a close eye on the patterns

According to research by USGS geophysicist Danny Brothers, portions of the Cascadia subduction zone, which stretches along the U.S. West Coast from northern California to northern Vancouver Island, are likely to have seen at least 30 significant earthquakes during the past 14,200 years. On average, a significant earthquake occurs there at least once every 450–500 years.

However, Cascadia has been silent for years; some scientists attribute this to the region being largely “locked” and under stress. A portion of the seafloor will rip and fall forward, possibly dozens of feet or more. A tsunami will come ashore due to the seafloor’s vertical displacement.

In the Cascadia subduction zone, additional information on slow-slip occurrences, enhanced fault zone mapping, and improved seafloor fault monitoring capabilities are needed to better comprehend the warning indications.

Actions, researches and quick response by U.S. scientists

Tobin was a member of the team that just created the most detailed map of the Cascadia subduction zone. They discovered that the fault is divided into four portions, each of which has the potential to rupture simultaneously or one at a time. Each of the separate segments has the potential to cause an earthquake of magnitude 8 or more.

In the interim, scientists are working to strengthen Cascadia’s offshore monitoring network. Although Japan is “one of the few places that has those instruments,” geophysicist David Schmidt of the University of Washington noted that the country has an advanced network of seafloor sensors.

While the United States lags behind other nations in seafloor monitoring, Schmidt and Tobin are members of a team that was awarded $10.6 million by the federal government to equip a fiber optic cable off the coast of Oregon with seismic sensors and seafloor pressure gauges.

The gadgets will be useful in monitoring Cascadia. If the information enables researchers to understand what constitutes normalcy for the defect, they may also be able to assess when concerns should be raised.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings